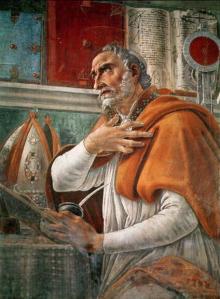

I’m increasingly interested in how John Chrysostom utilized Scripture, both in his biblical commentaries and otherwise. Like most other early Christian figures, Chrysostom does not spend much time explicitly setting forth his method of interpretation (notable exceptions include Origen’s On First Principles and Augustine’s On Christian Doctrine, among others), but in one of his homilies on Galatians 1, Chrysostom does divulge one of his most important principles for interpreting Scripture: attention to context.

I’m increasingly interested in how John Chrysostom utilized Scripture, both in his biblical commentaries and otherwise. Like most other early Christian figures, Chrysostom does not spend much time explicitly setting forth his method of interpretation (notable exceptions include Origen’s On First Principles and Augustine’s On Christian Doctrine, among others), but in one of his homilies on Galatians 1, Chrysostom does divulge one of his most important principles for interpreting Scripture: attention to context.

It is not the right course to consider words alone, or to examine the language by itself, because this will cause many errors. Rather we must consider the intention of the writer. And unless we follow this methodology in our own discussions, and look into the mind of the speaker, we will make many enemies, and everything will be thrown into confusion. This is not only true in regard to words, but we have the same result if we do not follow this rule when considering the actions of people. For example, surgeons often cut and break certain bones, and so do robbers. But it would be sad if we were not able to distinguish one from the other. Again, consider murderers and martyrs. When they are tortured, they suffer the same pains, yet the difference between them is very great. Unless we observe this rule, we will not be able to discriminate in these kinds of matters. Instead, we will end up calling Elijah and Samuel and Phineas murderers, and Abraham a murderer of his son. This will be the result if we go around scrutinizing bare facts without taking into account the intention of the participants.

In other words, the ancient and modern practice of “proof-texting,” of ripping out verses from their context as evidence for some view or another, is rejected in favor of careful attention to the context of the word or action. Particularly interesting is Chrysostom’s interest in “the intention of the writer,” which in some respects anticipates the more modern concern with authorial intent.

This passage falls in the midst of Chrysostom’s exposition of Gal 1:16-17. Here Chrysostom is concerned that Paul’s declaration that he did not go to Jerusalem to consult with the apostles there might be a sign of arrogance.

This expression when considered by itself can easily prove a stumbling-block and offensive to many hearers. But when it is kept in its context, everyone will agree with it and admire the speaker. So we shall do that… Let us then look at Paul’s intentions when he writes this. Let us consider his outlook and general conduct towards the apostles so that we may arrive at his meaning here.

Neither here nor previously did Paul speak with the intention of disparaging the apostles or of praising himself. How could he have intended to praise himself when he included himself in his condemnation? Rather, his only intention was to guard the integrity of the Gospel. Those troubling the church had said that they were obeying the apostles, who allowed these observances, and not Paul who forbade them. In this way the Judaizing heresy had gradually crept in. Now he needed to resist them resolutely, in order to check the arrogance of those who had improperly praised themselves, not, however, in order to speak against the apostles.

That is why he says, “I did not consult with any man.” It would have been extremely absurd for one who had been taught by God, afterwards to consult men. It is proper that someone who learns from men should in turn take advice from men. But why should someone who has been granted that divine and blessed voice, and who had been fully instructed by God, who possesses all the treasures of wisdom, later ask advice from men? It would be more fitting for him to teach others, not be taught by them. So Paul was not speaking arrogantly, but only showing the distinctiveness of his own commission. “Nor did I go up to Jerusalem,” he says, “to see those who were apostles before I was.” Because his opponents were continually repeating that the apostles were before him, and were called before him, he says, “I did not go visit them.” If he had needed to communicate with them, God, who revealed to him his commission, would have given him a command to do so.

Here, though, we encounter a problem which reveals a further point of Chrysostom’s method of interpretation: that Scripture interprets Scripture. As is well known, Paul’s declaration in Gal 1:17 that he did not go to Jerusalem to consult with the apostles immediately after his conversion appears to contradict the account in Acts 9:26, in which Paul immediately goes from Damascus to Jerusalem and meets with the apostles. Chrysostom anticipates this objection and resolves the problem in the following way:

Is it true, however, that he did not go to Jerusalem at all? No, he did go there, in fact, he went in order to learn something from them. But under what circumstance? A question arose on this subject in the city of Antioch, the church which had from the beginning shown so much zeal. They discussed whether or not the Gentile believers ought to be circumcised. In response, Paul went to Jerusalem along with Silas. So how can he say that he did not go up or confer with them? First, because he did not go up of his own accord, but was sent by others. Second, because he did not go to learn, but to change the opinions of others. From the very beginning his position was that which the apostles later confirmed, that circumcision was unnecessary. But when these people did not accept his position, and appealed to those at Jerusalem for support, Paul went up not to be instructed or corrected, but to convince the opposition that those at Jerusalem agreed with him. From the very first he understood from the proper mode of conduct, and needed no teacher. From the first, before any discussion took place, Paul maintained without wavering what the apostles, after much discussion later confirmed.

Luke shows Paul’s purpose in this journey in his account, where he relates that Paul argued at great length with them on this subject before he went to Jerusalem. But when the brothers chose to be informed on this matter by those at Jerusalem, Paul went up for their sake, not on his own. His expression, “nor did I go up,” means that he neither went at the beginning of his teaching ministry, nor in order to be instructed. Both are implied by the phrase, “I did not consult any man.” He does not merely say, “I did not consult,” but adds, “immediately.” And his later visit was not made to gain any additional instruction.

Now, we may find Chrysostom’s attempt to harmonize these texts more or less persuasive, but what is clear is his belief that all Scripture, inspired by the same Spirit, should be interpreted in such a way that it does not contradict other Scripture.

—Thanks to the Sacra Pagina blog for pointing me to this interesting text. Translation from Fourth Century Christianity.